火墨:在霾中呼吸--從墨性看當代山水畫語彙的重構

˙袁慧莉創作論述

一、楔子

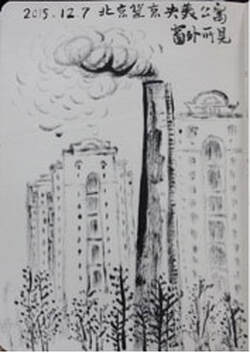

我在2015年12月09日抵達北京機場時,空氣中瀰漫灰濛濛的霧,這不是臺灣北方金山小鎮冬天雲氣裊繞的霧氣,而是正值北京發佈霧霾紅色警戒,全城籠罩在沈重的霧霾中,空氣中充滿了pm2.5的微細粒子。聽說北京一年中有非常多的時間都是籠罩在這樣的空氣品質之中,特別是冬天,因為家庭取暖燒爐,以及許多工廠排放黑煙,和北京車輛日漸增多的廢氣排放等問題,也是導致空氣品質一年不如一年的因素。而在北京一週之後回到臺灣時,又正好碰到北京霧霾在東北季風的吹引下移動到臺灣,這讓筆者感覺空氣無國界,隨著季風移動四處飄散。現今世界進入全球暖化危機造成地球溫度日漸上升的極端氣候現象,是21世紀人類面臨全球炭排放量失控的共同現實問題。

身處此時此刻的我,思考的是,山水畫作為一種對應自然世界題材的畫種,過往的內容往往表現人類居於自然山川之美的歌頌,或者是表達畫家心中的理想國或避世桃花源,但是,對於空汙如此不美的現實題材,則鮮少關注過。然而,當代山水畫之所以稱為當代,不能只是因為創作者是當代人這麼簡單的理由,而是指面對當代這個時空下的人事物所發生的議題,不再因循古典論述路線,而是需要思考如何透過議題性的思維,對現實處境進行創作表述,對古典論述進行有機的再論述或轉化,從而創造屬於當代語境的論述。於是,針對空氣與墨性議題,我在2015年獨創「火墨」觀點,包含理論架構與作品形式,都是全球獨創的新詞與墨性思維。以下將略述我的觀點。

二、火墨的燥墨對應傳統水墨的潤墨

在傳統的山水畫畫論美學中,水墨的氣韻生動是非常核心的美感追求,過往對於墨氣的要求是「墨不論濃淡乾濕,要不帶半點煙火食氣,思為極致。」[1]這種不食人間煙火的墨氣美學,是針對想要表現墨瀋氣韻淋漓的水墨畫時,透過筆墨與紙張之間的物性效果來傳達這種具有超脫於現實之理想的筆墨審美韻味。而對於積墨的審美「盎然溢然,冉冉欲墜,方烟潤不澀,深厚不薄」[2],可見對於墨氣的審美取向偏向於「潤」而非澀,因此用墨多半認為「燥澀乾枯而不潤」是不美的[3],這或許也是董其昌重南宗輕北宗的原因,因為南方的山水畫多半具有墨暈篇章、渾厚華滋、墨氣氤醞的特質。

在傳統山水畫論中,推崇「渾厚華滋」、「墨瀋淋漓」等等具有「潤墨」韻味的墨性美學,這種滋潤的墨趣成為歷來山水畫論的最高審美品味,例如唐杜甫詩:「元氣淋漓幛猶濕」[4];宋李成《山水訣》說過:「落墨無令太重,重則濁而不清;亦不可太輕,輕則燥而不潤。」[5];宋郭熙也曾在《林泉高致》裡細說用墨之法,要以「即墨色滋潤而不枯燥」為目標。元代黃公望更是重視用墨與深知用墨之難,同樣他的用墨美學也是追求「在生紙上,有許多滋潤處。」[6];明代唐志契談畫積墨於絹素之上要「方烟潤不澀」[7]。

上述這些古代畫論都主張以潤氣美學為主,而對於燥氣則多半不喜,只有到了清代龔賢認為「皴宜燥,不燥即墨矣」[8],但這裡的「燥」是乾筆、渴筆的意思,如同清末戴以恆(1826-1891) 在《醉蘇齋畫訣》裡有提到「燥筆、燥墨」的使用[9],他所說「燥筆微拖」、「用墨濕燥兩相同」[10],這個「燥」字多半指的是「乾筆」或「渴筆」的意思[11],而非筆者所指的火燒焦燥之燥氣。皴筆用燥(乾、渴),染墨用濕,所以傳統山水畫的山石主要是乾筆與濕墨之間皴染搭配的關係,經由這種乾濕對偶的搭配,山石的筆墨皴染得以具有「外潤而內有骨」[12]的效果。整體而言,中國傳統筆墨美學裡,「潤」是終極美學目標,「潤」指向「氣韻生動」的可能。

但是當21世紀實際生活中面對的不再僅僅是那種具有理想自然如桃花源般的滋潤世界,而是在霾害污染威脅下的環境,顯然水墨強調超然物外、氣韻生動、墨瀋淋漓的山水樣貌,某種程度上並不能完全符合現實生活當下的真實感知,如何以山水畫形式對於這個全球暖化問題提出批判和反映?更且如何從「墨性」材質路徑審思,重新思考如何以當代真實情境對比古典山水畫美學之變異,以因應當代世界樣貌,這是我2015年從北京經驗之後思索的重點。

原本在「水墨為上」中的用「水」元素,在清代被視為「筆墨作何生動,妙在用水」[13]、「作畫不善用水,件件醜惡」[14],滋潤的筆墨技術被視為重要的筆墨美學範疇,但是,一旦想要表達真實世界的醜陋,墨暈篇章的水墨恐怕並不能貼切的彰顯當代世界氣候暖化焦燥空汙的社會現象。而水墨畫一向以來總是躲在安適的世外桃源,與現實世界產生隔離,無法貼近真實生活的這種問題總是為人所詬病,正是水墨這種材質無法跨越其限制,而使水墨畫總是在追求理想性的「自然美」為主,囿於既定的筆墨思維中而脫離現實。事實上,除了關注於水墨的筆墨如何與時並進之外,當面對21世紀自然世界被破壞的議題時,另一種關於如何突破水墨畫舊有的筆墨美學侷限,亦是需要思考的部分。當地球暖化,空氣中彌漫的是一種焦「燥」氣,而非水墨淋漓滋潤之氣時,我需要以新的方法來傳達在傳統畫論中較少宣揚的火氣「焦燥」,而非「墨瀋淋漓幛猶濕」的水墨潤性美學。

三、火墨的墨性美學與材質方法

因此,為了更貼近當今21世紀地球暖化空污現象,我提出《火墨系列》作品作為當代另一種墨性語彙的重構。我以「火墨」的「燥氣」取代「水墨」的「潤氣」,來作為對當下環境氣候變異狀態的回應。

所謂「火墨」指的是以火作為媒介,而非以水作為媒介的創作方法,「火墨」對應於「水墨」,不僅是墨性美學的反轉,更是材料學上的突破,這是涉及材料文化學的邏輯辯證,我將宣紙經過火燒之後所得的宣紙炭灰取代水墨的墨條,作為換置古典山水畫的使用材料。

從材料面來看, 水墨的本質來自於墨與水兩者的調和,原本作為與水調和的墨條,是來自燃燒樹木後取得的炭灰,經過加入動物膠的揉製捶打後製成人造文化物。而宣紙製程的原物料也是來自樹皮或植物,這點和墨的原料相似,不同的是,宣紙製造過程中,樹皮是經過水浸泡後打漿等過程手抄成人造文化物。因此,同樣來源於樹的原料,但墨條先經過火的過程再與水調和,而宣紙則是先經過水的過程再被我以火還原為炭灰,樹、水與火這三種自然元素,同樣都曾作用於火墨與水墨的材料之中,只是其先後次序不同,因此結果不同。火墨使用宣紙炭灰的作法,其實便是將本質為樹皮的宣紙還原為如同墨的炭灰,只是紙灰顆粒較大,這種紙灰餘燼能夠貼切地用以象徵同為燃燒剩餘物的霧霾。

除了使用宣紙炭灰之外,我還會將宣紙卷成筆狀,在畫的時候邊燒邊畫,這種卷筆可以處理較細部的線條,就好像毛筆舔沾硯臺裡磨好的墨汁,紙卷筆則是舔以蠟燭的火燒,這是以火置換水的繪畫過程。我不僅在材料上「換置」[15],也在圖像上進行「換置」,將古典象徵潤墨氣韻的圖像重新以火墨臨摹,在2015年12月第一件火墨作品《火墨早春圖no.1》,臨摹的對象就是最能代表古典山水畫空氣潤墨的北宋郭熙《早春圖》,後來在2017年於台北內湖耿畫廊的「墨的兩種呼吸方式」個展中所有火墨作品,也都是選擇古典山水畫中以氣候或者季節為題材的經典作品進行對臨換置的創作,並在其原有標題上加上「火墨」二字。

選擇北宋郭熙《早春圖》,以及其他火墨所臨摹的古典作品,這些古典作品裡的水墨表現都有共同的墨性特徵,都是指向空氣中萬物蒸騰的水氣景象以及滋潤氣候韻致,這些山水畫以墨性表現理想的自然世界、一個極美好而和諧的山水景象,如同世外桃源般令人嚮往居遊其中。郭熙《早春圖》歌頌宋朝治理之下的國家秩序,以及仁君治下的民安樂居世界,這幅畫的圖像已經成為一個經典的符號,代表着自然與人類「天人合一」的理想山水境界意涵。作為火墨換置的對象,使用宣紙炭灰取代了水墨,材質的還原與轉換,帶動了原本經典圖像美學的內部意涵也跟著轉化。從水墨的濕筆潤墨轉化成為火墨焦炭燥筆,意指經過了千年,地球從農業時代演進向工業時代,原本水墨滋潤的自然世界已被當代不斷燃燒的廢氣與灰塵所覆蓋。

挪用進而以材質換置經典圖像不是為了重複古典筆墨的審美目的,而是透過物質的還原彰顯在當代人類的生活面向所面臨的社會問題,凸顯當代世界的氣候與空氣取代了遠古尚未受到工業污染時期的美好自然世界,《火墨系列》作品不是為了再現傳統筆墨藝術視角的摹仿創作,而是為了彰顯當代創作者的身體感知,所進行的繪畫語境反思。我希望我的《火墨系列》不僅僅在材質形式上更新傳統,更希望進一步置入山水畫內部意涵更深沈的當代視角,而不僅僅只是侷限在表現古典自然觀美學的理想世界。

《火墨系列》使用炭灰這種容易飄動的材料,決不使用任何水性的膠加以固定在宣紙上,因此,火墨作品中的炭灰有移動的可能,這種移動狀態象徵著空氣中的霾炭懸浮物質飄散在空氣中隨時變換位置,正如台灣的霾有部分來自境外,而工廠的廢棄也是飄散的狀態。某些火墨作品以裝置形式進行現場展示,或者使用壓克力箱框裡放置燃燒過的紙卷,灼紙卷象徵排放空汙的煙囪,紙炭灰象徵霧霾中無處不在的炭微粒。這種透明的箱框如同載滿空氣的「天地之器」,內部放置的燃燒紙卷隱喻煙囪,象徵所燒的焦躁灰燼使山水蒙上燥墨,透明箱中的底部還留有飄散的炭灰。

火墨系列主要對應於有關當今空氣污染議題,因此所臨摹的古典山水圖像,主要選用帶有氣候、季節、時令的標題,或者具空氣感、水墨性的古圖為主,來與「火墨」觸及的空氣議題進行對應。這是試圖以火墨取代水墨圖像時,帶出古今時空移轉後,氣候變遷下空氣清濁的對比。火墨系列作為觀念性作品,不僅以行為展演古畫今臨,凸顯氣候變遷下空汙議題,更以裝置手法加強觀念的呈現,而這些都在2017年於耿畫廊個展中具體呈現。

四、小結

盛行了一千年的水墨美學,到了現代水墨畫運動也仍然強調著水與潤的重要性,其墨性美學語彙並未更新古典的範疇。而 「火墨」透過材質的還原與轉換,則前衛地進入古典從未觸及的「火墨」墨性領域,原本水墨的潤氣被「火墨」的燥氣所取代,這樣的「換置」創作,象徵著21世紀的工業世界取代了11世紀農業時代的空氣,同時也投射出傳統的水墨材質與美學語境,在反映當下生存環境的真實感受時有其侷限性,因此,墨性型態與美學語彙在21世紀有其拓展的必要。不再以「水」墨為唯一的表現途徑,在這個充滿燥氣的時代,「火」所象徵的乾灼之燥,以及其隱喻著工業時代,普遍存在於生活環境周遭的火氣、廢氣、熱氣、碳排放等等現象,「火墨」山水畫才能貼切的反映此時代有關「空氣」議題的真實墨性。 在儀式性的現場行為創作與祭祀性的裝置型式,彷彿隱喻著當代生存者佇立在古典水墨殘存的勝景灰燼中,像是對傳統山水語境歷史進行唏噓奠祭。而也正是提出此一新的墨性語彙與型態,墨性美學才得以真正地進入當代語境。

[1] 清張庚,《圖畫精意識畫論》,見傅抱石,《中國繪畫理論》,頁115。

[2] 明唐志契,《繪事微言》,見俞崑編,《中國畫論類編》下卷,頁747。

[3] 宋李成,《畫山水訣》,見俞崑編,《中國畫論類編》上卷,頁620。

[4] 杜甫詩:〈奉先劉少府新畫山水幛歌〉裡的詩句,形容筆墨酣暢飽滿。唐代畫山水用絹,因此濕筆多,故杜甫以「淋漓」、「猶濕」來形容其筆墨。

[5] 《山水訣》傳為李成所作,引自俞崑,《中國畫論類編》上卷,頁616。

[6] 元,黃公望,《寫山水訣》,引自俞崑,《中國畫論類編》下卷,頁699。

[7] 明,唐志契,《繪事微言》,引自俞崑,《中國畫論類編》下卷,頁699。

[8] 清龔賢,《半千課徒畫說》,見俞崑編,《中國畫論類編》下卷,頁797。

[9] 清,戴以恆,《醉蘇齋畫訣》「用墨法」:「須用燥筆如睡醒。…燥筆濃墨略有痕」

[10] 清戴以恆,《醉蘇齋畫訣》,見俞崑編,《中國畫論類編》下卷,頁1004、1 007。

[11] 如提到「用墨法」:「用墨濕燥兩相同,燥來顏色分淡濃,何為燥濕兩相同?紙上已燥墨色濃,濕墨上紙顏色同,到燥之後淡一重。層層濕燥遞相加,人墨枯燥我獨華。」引同上註。

[12] 同上註,頁796。

[13] 李鱔,《頤園論畫》,轉引自羅穎,〈筆墨與色彩〉,頁223。收于中國美術學院中國畫系編,《形神與筆墨:中國畫學研究》,杭州:中國美術學院出版社,2008,頁222-225。

[14] 同上註。

[15] 「換置」hypallage一詞源自古希臘,文學修辭法的一種,意指將字詞移花接木,「狀語中形容詞與名詞的位置調換,修飾語後移,被修飾詞前移,這使得句義產生錯誤的偏離」,使原本語句結構發生邏輯上的變化。「換置」不同於「挪用」,「挪用」是指「直接複製、抄襲、採用他人的圖像作品,改變其原創性與真確性」,而「換置」則除了可涉及「挪用」,更進一步移換其中造形語法元素與結構邏輯,不僅改變其原創性,更使其內在意義產生變異與間隙,以達到拓展置入新意涵詮釋的可能。

一、楔子

我在2015年12月09日抵達北京機場時,空氣中瀰漫灰濛濛的霧,這不是臺灣北方金山小鎮冬天雲氣裊繞的霧氣,而是正值北京發佈霧霾紅色警戒,全城籠罩在沈重的霧霾中,空氣中充滿了pm2.5的微細粒子。聽說北京一年中有非常多的時間都是籠罩在這樣的空氣品質之中,特別是冬天,因為家庭取暖燒爐,以及許多工廠排放黑煙,和北京車輛日漸增多的廢氣排放等問題,也是導致空氣品質一年不如一年的因素。而在北京一週之後回到臺灣時,又正好碰到北京霧霾在東北季風的吹引下移動到臺灣,這讓筆者感覺空氣無國界,隨著季風移動四處飄散。現今世界進入全球暖化危機造成地球溫度日漸上升的極端氣候現象,是21世紀人類面臨全球炭排放量失控的共同現實問題。

身處此時此刻的我,思考的是,山水畫作為一種對應自然世界題材的畫種,過往的內容往往表現人類居於自然山川之美的歌頌,或者是表達畫家心中的理想國或避世桃花源,但是,對於空汙如此不美的現實題材,則鮮少關注過。然而,當代山水畫之所以稱為當代,不能只是因為創作者是當代人這麼簡單的理由,而是指面對當代這個時空下的人事物所發生的議題,不再因循古典論述路線,而是需要思考如何透過議題性的思維,對現實處境進行創作表述,對古典論述進行有機的再論述或轉化,從而創造屬於當代語境的論述。於是,針對空氣與墨性議題,我在2015年獨創「火墨」觀點,包含理論架構與作品形式,都是全球獨創的新詞與墨性思維。以下將略述我的觀點。

二、火墨的燥墨對應傳統水墨的潤墨

在傳統的山水畫畫論美學中,水墨的氣韻生動是非常核心的美感追求,過往對於墨氣的要求是「墨不論濃淡乾濕,要不帶半點煙火食氣,思為極致。」[1]這種不食人間煙火的墨氣美學,是針對想要表現墨瀋氣韻淋漓的水墨畫時,透過筆墨與紙張之間的物性效果來傳達這種具有超脫於現實之理想的筆墨審美韻味。而對於積墨的審美「盎然溢然,冉冉欲墜,方烟潤不澀,深厚不薄」[2],可見對於墨氣的審美取向偏向於「潤」而非澀,因此用墨多半認為「燥澀乾枯而不潤」是不美的[3],這或許也是董其昌重南宗輕北宗的原因,因為南方的山水畫多半具有墨暈篇章、渾厚華滋、墨氣氤醞的特質。

在傳統山水畫論中,推崇「渾厚華滋」、「墨瀋淋漓」等等具有「潤墨」韻味的墨性美學,這種滋潤的墨趣成為歷來山水畫論的最高審美品味,例如唐杜甫詩:「元氣淋漓幛猶濕」[4];宋李成《山水訣》說過:「落墨無令太重,重則濁而不清;亦不可太輕,輕則燥而不潤。」[5];宋郭熙也曾在《林泉高致》裡細說用墨之法,要以「即墨色滋潤而不枯燥」為目標。元代黃公望更是重視用墨與深知用墨之難,同樣他的用墨美學也是追求「在生紙上,有許多滋潤處。」[6];明代唐志契談畫積墨於絹素之上要「方烟潤不澀」[7]。

上述這些古代畫論都主張以潤氣美學為主,而對於燥氣則多半不喜,只有到了清代龔賢認為「皴宜燥,不燥即墨矣」[8],但這裡的「燥」是乾筆、渴筆的意思,如同清末戴以恆(1826-1891) 在《醉蘇齋畫訣》裡有提到「燥筆、燥墨」的使用[9],他所說「燥筆微拖」、「用墨濕燥兩相同」[10],這個「燥」字多半指的是「乾筆」或「渴筆」的意思[11],而非筆者所指的火燒焦燥之燥氣。皴筆用燥(乾、渴),染墨用濕,所以傳統山水畫的山石主要是乾筆與濕墨之間皴染搭配的關係,經由這種乾濕對偶的搭配,山石的筆墨皴染得以具有「外潤而內有骨」[12]的效果。整體而言,中國傳統筆墨美學裡,「潤」是終極美學目標,「潤」指向「氣韻生動」的可能。

但是當21世紀實際生活中面對的不再僅僅是那種具有理想自然如桃花源般的滋潤世界,而是在霾害污染威脅下的環境,顯然水墨強調超然物外、氣韻生動、墨瀋淋漓的山水樣貌,某種程度上並不能完全符合現實生活當下的真實感知,如何以山水畫形式對於這個全球暖化問題提出批判和反映?更且如何從「墨性」材質路徑審思,重新思考如何以當代真實情境對比古典山水畫美學之變異,以因應當代世界樣貌,這是我2015年從北京經驗之後思索的重點。

原本在「水墨為上」中的用「水」元素,在清代被視為「筆墨作何生動,妙在用水」[13]、「作畫不善用水,件件醜惡」[14],滋潤的筆墨技術被視為重要的筆墨美學範疇,但是,一旦想要表達真實世界的醜陋,墨暈篇章的水墨恐怕並不能貼切的彰顯當代世界氣候暖化焦燥空汙的社會現象。而水墨畫一向以來總是躲在安適的世外桃源,與現實世界產生隔離,無法貼近真實生活的這種問題總是為人所詬病,正是水墨這種材質無法跨越其限制,而使水墨畫總是在追求理想性的「自然美」為主,囿於既定的筆墨思維中而脫離現實。事實上,除了關注於水墨的筆墨如何與時並進之外,當面對21世紀自然世界被破壞的議題時,另一種關於如何突破水墨畫舊有的筆墨美學侷限,亦是需要思考的部分。當地球暖化,空氣中彌漫的是一種焦「燥」氣,而非水墨淋漓滋潤之氣時,我需要以新的方法來傳達在傳統畫論中較少宣揚的火氣「焦燥」,而非「墨瀋淋漓幛猶濕」的水墨潤性美學。

三、火墨的墨性美學與材質方法

因此,為了更貼近當今21世紀地球暖化空污現象,我提出《火墨系列》作品作為當代另一種墨性語彙的重構。我以「火墨」的「燥氣」取代「水墨」的「潤氣」,來作為對當下環境氣候變異狀態的回應。

所謂「火墨」指的是以火作為媒介,而非以水作為媒介的創作方法,「火墨」對應於「水墨」,不僅是墨性美學的反轉,更是材料學上的突破,這是涉及材料文化學的邏輯辯證,我將宣紙經過火燒之後所得的宣紙炭灰取代水墨的墨條,作為換置古典山水畫的使用材料。

從材料面來看, 水墨的本質來自於墨與水兩者的調和,原本作為與水調和的墨條,是來自燃燒樹木後取得的炭灰,經過加入動物膠的揉製捶打後製成人造文化物。而宣紙製程的原物料也是來自樹皮或植物,這點和墨的原料相似,不同的是,宣紙製造過程中,樹皮是經過水浸泡後打漿等過程手抄成人造文化物。因此,同樣來源於樹的原料,但墨條先經過火的過程再與水調和,而宣紙則是先經過水的過程再被我以火還原為炭灰,樹、水與火這三種自然元素,同樣都曾作用於火墨與水墨的材料之中,只是其先後次序不同,因此結果不同。火墨使用宣紙炭灰的作法,其實便是將本質為樹皮的宣紙還原為如同墨的炭灰,只是紙灰顆粒較大,這種紙灰餘燼能夠貼切地用以象徵同為燃燒剩餘物的霧霾。

除了使用宣紙炭灰之外,我還會將宣紙卷成筆狀,在畫的時候邊燒邊畫,這種卷筆可以處理較細部的線條,就好像毛筆舔沾硯臺裡磨好的墨汁,紙卷筆則是舔以蠟燭的火燒,這是以火置換水的繪畫過程。我不僅在材料上「換置」[15],也在圖像上進行「換置」,將古典象徵潤墨氣韻的圖像重新以火墨臨摹,在2015年12月第一件火墨作品《火墨早春圖no.1》,臨摹的對象就是最能代表古典山水畫空氣潤墨的北宋郭熙《早春圖》,後來在2017年於台北內湖耿畫廊的「墨的兩種呼吸方式」個展中所有火墨作品,也都是選擇古典山水畫中以氣候或者季節為題材的經典作品進行對臨換置的創作,並在其原有標題上加上「火墨」二字。

選擇北宋郭熙《早春圖》,以及其他火墨所臨摹的古典作品,這些古典作品裡的水墨表現都有共同的墨性特徵,都是指向空氣中萬物蒸騰的水氣景象以及滋潤氣候韻致,這些山水畫以墨性表現理想的自然世界、一個極美好而和諧的山水景象,如同世外桃源般令人嚮往居遊其中。郭熙《早春圖》歌頌宋朝治理之下的國家秩序,以及仁君治下的民安樂居世界,這幅畫的圖像已經成為一個經典的符號,代表着自然與人類「天人合一」的理想山水境界意涵。作為火墨換置的對象,使用宣紙炭灰取代了水墨,材質的還原與轉換,帶動了原本經典圖像美學的內部意涵也跟著轉化。從水墨的濕筆潤墨轉化成為火墨焦炭燥筆,意指經過了千年,地球從農業時代演進向工業時代,原本水墨滋潤的自然世界已被當代不斷燃燒的廢氣與灰塵所覆蓋。

挪用進而以材質換置經典圖像不是為了重複古典筆墨的審美目的,而是透過物質的還原彰顯在當代人類的生活面向所面臨的社會問題,凸顯當代世界的氣候與空氣取代了遠古尚未受到工業污染時期的美好自然世界,《火墨系列》作品不是為了再現傳統筆墨藝術視角的摹仿創作,而是為了彰顯當代創作者的身體感知,所進行的繪畫語境反思。我希望我的《火墨系列》不僅僅在材質形式上更新傳統,更希望進一步置入山水畫內部意涵更深沈的當代視角,而不僅僅只是侷限在表現古典自然觀美學的理想世界。

《火墨系列》使用炭灰這種容易飄動的材料,決不使用任何水性的膠加以固定在宣紙上,因此,火墨作品中的炭灰有移動的可能,這種移動狀態象徵著空氣中的霾炭懸浮物質飄散在空氣中隨時變換位置,正如台灣的霾有部分來自境外,而工廠的廢棄也是飄散的狀態。某些火墨作品以裝置形式進行現場展示,或者使用壓克力箱框裡放置燃燒過的紙卷,灼紙卷象徵排放空汙的煙囪,紙炭灰象徵霧霾中無處不在的炭微粒。這種透明的箱框如同載滿空氣的「天地之器」,內部放置的燃燒紙卷隱喻煙囪,象徵所燒的焦躁灰燼使山水蒙上燥墨,透明箱中的底部還留有飄散的炭灰。

火墨系列主要對應於有關當今空氣污染議題,因此所臨摹的古典山水圖像,主要選用帶有氣候、季節、時令的標題,或者具空氣感、水墨性的古圖為主,來與「火墨」觸及的空氣議題進行對應。這是試圖以火墨取代水墨圖像時,帶出古今時空移轉後,氣候變遷下空氣清濁的對比。火墨系列作為觀念性作品,不僅以行為展演古畫今臨,凸顯氣候變遷下空汙議題,更以裝置手法加強觀念的呈現,而這些都在2017年於耿畫廊個展中具體呈現。

四、小結

盛行了一千年的水墨美學,到了現代水墨畫運動也仍然強調著水與潤的重要性,其墨性美學語彙並未更新古典的範疇。而 「火墨」透過材質的還原與轉換,則前衛地進入古典從未觸及的「火墨」墨性領域,原本水墨的潤氣被「火墨」的燥氣所取代,這樣的「換置」創作,象徵著21世紀的工業世界取代了11世紀農業時代的空氣,同時也投射出傳統的水墨材質與美學語境,在反映當下生存環境的真實感受時有其侷限性,因此,墨性型態與美學語彙在21世紀有其拓展的必要。不再以「水」墨為唯一的表現途徑,在這個充滿燥氣的時代,「火」所象徵的乾灼之燥,以及其隱喻著工業時代,普遍存在於生活環境周遭的火氣、廢氣、熱氣、碳排放等等現象,「火墨」山水畫才能貼切的反映此時代有關「空氣」議題的真實墨性。 在儀式性的現場行為創作與祭祀性的裝置型式,彷彿隱喻著當代生存者佇立在古典水墨殘存的勝景灰燼中,像是對傳統山水語境歷史進行唏噓奠祭。而也正是提出此一新的墨性語彙與型態,墨性美學才得以真正地進入當代語境。

[1] 清張庚,《圖畫精意識畫論》,見傅抱石,《中國繪畫理論》,頁115。

[2] 明唐志契,《繪事微言》,見俞崑編,《中國畫論類編》下卷,頁747。

[3] 宋李成,《畫山水訣》,見俞崑編,《中國畫論類編》上卷,頁620。

[4] 杜甫詩:〈奉先劉少府新畫山水幛歌〉裡的詩句,形容筆墨酣暢飽滿。唐代畫山水用絹,因此濕筆多,故杜甫以「淋漓」、「猶濕」來形容其筆墨。

[5] 《山水訣》傳為李成所作,引自俞崑,《中國畫論類編》上卷,頁616。

[6] 元,黃公望,《寫山水訣》,引自俞崑,《中國畫論類編》下卷,頁699。

[7] 明,唐志契,《繪事微言》,引自俞崑,《中國畫論類編》下卷,頁699。

[8] 清龔賢,《半千課徒畫說》,見俞崑編,《中國畫論類編》下卷,頁797。

[9] 清,戴以恆,《醉蘇齋畫訣》「用墨法」:「須用燥筆如睡醒。…燥筆濃墨略有痕」

[10] 清戴以恆,《醉蘇齋畫訣》,見俞崑編,《中國畫論類編》下卷,頁1004、1 007。

[11] 如提到「用墨法」:「用墨濕燥兩相同,燥來顏色分淡濃,何為燥濕兩相同?紙上已燥墨色濃,濕墨上紙顏色同,到燥之後淡一重。層層濕燥遞相加,人墨枯燥我獨華。」引同上註。

[12] 同上註,頁796。

[13] 李鱔,《頤園論畫》,轉引自羅穎,〈筆墨與色彩〉,頁223。收于中國美術學院中國畫系編,《形神與筆墨:中國畫學研究》,杭州:中國美術學院出版社,2008,頁222-225。

[14] 同上註。

[15] 「換置」hypallage一詞源自古希臘,文學修辭法的一種,意指將字詞移花接木,「狀語中形容詞與名詞的位置調換,修飾語後移,被修飾詞前移,這使得句義產生錯誤的偏離」,使原本語句結構發生邏輯上的變化。「換置」不同於「挪用」,「挪用」是指「直接複製、抄襲、採用他人的圖像作品,改變其原創性與真確性」,而「換置」則除了可涉及「挪用」,更進一步移換其中造形語法元素與結構邏輯,不僅改變其原創性,更使其內在意義產生變異與間隙,以達到拓展置入新意涵詮釋的可能。

2017年耿畫廊個展火墨系列作品各種裝置型態